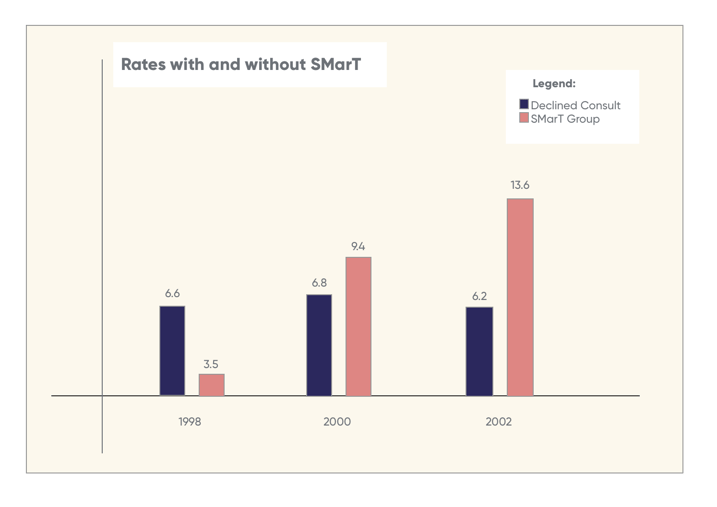

When Thaler and Benartzi designed the Save More Tomorrow program (SMarT), the results were outstanding. The program took advantage of commitment devices to get employees to commit to putting away a higher percentage of their overall wealth after each pay raise. By keeping in mind key human biases and bounded rationality when it comes to saving for the future, the program was simple yet effective.

Over 4 years it was clear that those who were a part of the SMarT group saved at a far higher rate than those who were not. The increase in savings continued even after a fourth pay raise.

With the above success using psychological principles and behavioral data for an individual financial plan, it's clear that other regulation and financial policies can reap massive benefits by using Behavioural Science.

In particular, how can banking regulatory policy be optimised?

Institutions, much like humans rarely act in predicted rational ways. Even the most agile companies have processes that are culturally ingrained and difficult to change. Traditional command and control mechanisms have been proven time and again to be ineffective. Often a friendlier nudge can deliver better results.

By analysing past patterns of investors and institutions, regulators can enhance their financial supervision. Internally, banks can do the same with their own internal and customer data. Behavioural science can improve areas such as investor protection, education, messaging, and ultimately enhance policies, regulation, and compliance.

The United Kingdom has been a leader in the space of incorporating behavioural science into governmental policies and regulation with their innovative Behavioral Insights Team.

The UK’s FCA currently uses behavioral science to influence their financial policies, and this is seen across other markets such as the Netherlands, Canada, Australia and Singapore. While some policies are starting to be designed with behavioural principles in mind, these markets have not fully taken advantage of what Behavioral Science can achieve.

Behavioral Science can go further to improve regulatory compliance.

1) Making compliance a social norm

Regulators would benefit by thinking of humans as herd animals. We like to assess our own behaviour in relation to those around us. Social norms can be explicit or observed by the actions of others, driving us to conform to social expectations.

Positive --and unfortunately negative-- behavior can be socially contagious. For example, Gino, Ayal, and Ariely found that acting dishonestly can become a social norm. If a group observed a perceived member of their in-group cheating and then being rewarded, members of the group were far more likely to also cheat. Their experiment was created to examine how dishonesty can infiltrate a corporate culture; Ariely has suggested that US Bank Wells Fargo’s sales culture had been negatively affected by contagious dishonest behavior.

Future regulations should consider that norms influence an individual’s decision making process. When trying to change a behavior, it is not as simple as stating a legal rule. For example, whistleblower policies must be sympathetic to the effort it takes for a person to go against their peers. Offering incentives and ensuring privacy could help employees to come forward. To get a group of individuals to change their behavior, regulators must think about entire systems and not single actors. While norms are not the only way that an individual plans their behavior, it is a very influential area that could be leveraged to spur compliance.

2) Understanding that humans misjudge their future self

Even when motivation is high for companies to adhere to new regulation, human error can always prevent intended compliance. Think about the last time you broke a new year's resolution- often we think we will be our best future self and forget about the various obstacles we face today. This is the planning fallacy, we tend to underestimate the time and cost needed to accomplish our future actions.

Designing the messaging around a new policy with these biases in mind, will lead to drastically better customer outcomes.

For example, banks changing a policy should consider whether a deadline is 2 years or 10 days away and should then appropriately communicate that urgency to their customers. If a deadline is far in the future, a more progressive communication system that starts early, but gets rapidly more warm would be far better at getting customers to understand and act. The timing of a nudge matters and the messaging should be tailored accordingly.

3) Taking advantage of commitments

Simply by affirming your commitment to do something ultimately makes it more likely to complete a future goal. By getting teams to agree to do new compliance actions beforehand, they are more likely to change their behavior. Using small micro-commitments before changing a larger action can serve as a way to nudge a desired compliance behavior. This is illustrated by a study that found neighbors to be more likely to agree to a large sign in their front yard if they had already agreed to place a small card in their window supporting safer driving. This foot-in-the-door technique can be similarly used to elicit other desired behaviors.

Financial institutions enacting new compliance policies could try using these micro-commitments to softly nudge their employees. It is a simple way to remind each individual actor to plan to change their behavior to properly comply with new regulations. For example, having a team agree to a new practice and write their plan and sign it would lead to more members remembering to do the new action and feeling more positively about the act after.

Conclusion

The key point of this article is to highlight the importance of designing regulatory policies with irrational institutions in mind. Institutions, just like humans, can be irrational and can benefit from smartly designed policies. It is much easier to roll a ball down a hill than to push it up, when you design a policy understanding key biases, you are working with a force like gravity instead of against it.

At Cowry we have worked with some of the world’s largest brands to help create incredible behavioural science-based regulation-based initiatives. We would love to work with your company and help you do the same, so let’s have a conversation.

References:

Emiliani, Bob (2020). Irrational Institutions. South Kingstown, RI: Cubic LLC

Freedman, J. L., & Fraser, S. C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: the foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of personality and social psychology, 4(2), 195.

Gino, F., Ayal, S., & Ariely, D. (2009). Contagion and differentiation in unethical behavior: The effect of one bad apple on the barrel. Psychological science, 20(3), 393-398.

Kreps, C. (1966). Modernizing Banking Regulation. Law and Contemporary Problems, 31(4), 648-672. doi:10.2307/1190829

Pete, L. (2014). Regulatory policy and behavioural economics. OECD publishing.

Sjöstrand, S. E. (1992). On the Rationale behind" Irrational" Institutions. Journal of Economic Issues, 26(4), 1007-1040.

Thaler, R. H., & Benartzi, S. (2004). Save more tomorrow™: Using behavioral economics to increase employee saving. Journal of political Economy, 112(S1), S164-S187.