Introduction

When the Apple AirPods first launched in 2016, the whole world made fun of the headphones' innovative design. People on the internet did what they do best: They created memes comparing the regular AirPods to electric toothbrush heads and the AirPod Pro's to Battle Droids.

Now, 6 years later, you see them everywhere. People have entirely changed their minds and the AirPods are currently one of the most popular headphones on the market.

Since Behavioural Scientists have a curious nature, the question arises: What is the psychological basis for people initially hating an innovative design and learning to love it over time?

….. and what can your organisation learn from all of this? (But we will answer that question a little later)

The Psychological basis

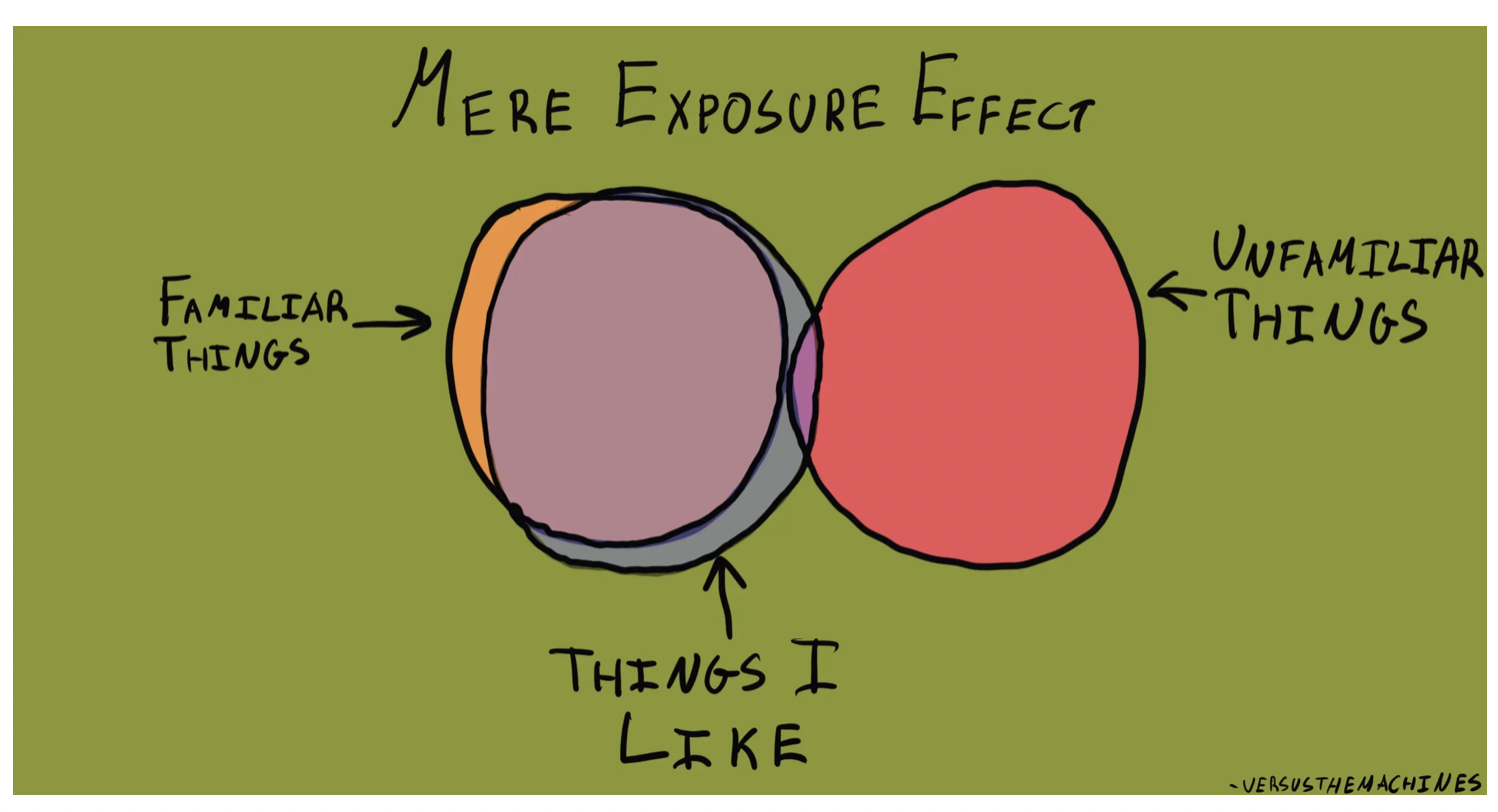

It is common knowledge that people generally like what looks and feels familiar. This is because familiar objects or faces can be processed fluently by our brain, which feels good to us. Therefore, the more fluidly something can be processed, the more attractive it is.

The mere-exposure effect even states that we like objects more simply when we are exposed to them multiple times. However, what Behavioural Scientists discuss less often is that there is also a downside to the mere-exposure effect. Which is boredom. Over time people can actually grow quite bored of products, especially when they have simple patterns and uninventive designs.

When consumers get tired of your product, it is probably a good time to launch something new. Before a new product is launched, user research is usually conducted to minimise the risk of failure and to increase the chances of success. The standard process of user research involves focus groups, questionnaires or simple evaluations, which are usually done only once. Measuring something only once is fine if you assume it is static. However, this is not the case with innovative products such as cars, phones or - as in the case of Apple - headphones.

If we think about it, does it make sense to ask users for a rating only once when in real life they will repeatedly engage with your product over a longer period of time? For this reason, researchers have conducted experiments with what they call the "repeated evaluation technique" (Carbon & Leder, 2005). They found that the evaluation of the attractiveness of innovative products is not static, but a very dynamic process between user and product. Rather than asking users to rate products only once, they asked them to engage intensively with innovative and non-innovative designs and rate their attractiveness repeatedly over a longer period of time.

What they found was astonishing: people initially had a strong aversion to innovative designs, but after they had engaged with the products, the scores for the attractiveness of these products increased significantly. On the other hand, the perceived attractiveness of non-innovative design actually decreased over time.

A year after the first study, they also found that innovative designs were not only more cognitively demanding for users, but also generated more interest (Carbon et al., 2006). Innovative designs are interesting because they force us to break our habitual ways of seeing and our expectations of a product. For example: “Why do these headphones look like toothbrush heads?”. Asking ourselves these kinds of questions requires a certain cognitive effort, which is why we often don't like innovative designs when we first see them.

But there is more to the story. Another reason we grow weary of non-innovative designs is when they lack social meaning, and this lack of deeper meaning reinforces the feeling of boredom over time (Barbalet, 1999). More specifically, Barbalet believes that boredom acts as a signal to tell us that something is not meaningful to us. In this he makes a clear distinction between habits and boredom, where habits are a means to an end and therefore meaningful. However, when actions lose their purpose or function, they become meaningless and thus boring. We can therefore assume that a product ultimately becomes boring if it is neither interesting to look at nor fulfils a function or purpose anymore.

What does this mean for behavioural product design?

An interesting application area for these findings could be behaviourally designed sustainable products such as water bottles, reusable shopping bags or vegetable nets. Firstly, you want people to use these products in the long term, and secondly, innovative design is a good way to attract attention and thus create awareness for sustainability in general. And finally, these objects have a deeper social meaning. Their sustainable character is our personal contribution to reducing plastic waste; therefore, the innovative design of these products could lead to a lasting change in behaviour by people using them habitually over a long period of time. There are already innovative designs out there that can serve as examples, like the City Harvests ‘Empty Stomach Bag’, the ‘Global Action in the Interest of Animals Bag’ or this backpack that is made only out of natural and eco-friendly materials.

Going beyond this, designers should take into consideration the user’s interaction with the product. In the case of AirPods, whilst the uniqueness of its design successfully captures consumer’s attention and interest, the seamless interaction and personalisation features are those that promote user’s engagement and experience with the product. Hence, it is crucial to think about not only the product’s design alone but also how people interact with this design. In that way, it’s possible to create an exceptional, memorable user experience.

Conclusions

Product designers should not be afraid to be innovative, even if users' initial reactions may be negative. And when conducting user research, instead of collecting one-time measurements, researchers should give consumers enough time to really engage with the product and ask them to evaluate the product repeatedly.

The same applies to the launch of your product. Even if consumers react badly to your innovative design at first, they may learn to love it all the more over time.

We can therefore conclude that a good mix of deeper meaning, cognitively sophisticated design and rebellious features of functions put together in a coherent and harmonious way could put you on the right track for consumers to love your products in the long run.

References

Barbalet, J.M. (1999) Boredom and social meaning. British Journal of Sociology (50) 631–646.

Carbon, C.C., Leder, H. (2005). The repeated evaluation technique (RET). A method to capture dynamic effects of innovativeness and attractiveness. Applied Cognitive Psychology (19) 587–601.

Carbon, C.C., Hutzler, F., Minge, M. (2006) Innovation in design investigated by eye movements and pupillometry. Psychological Science (48) 173–186.

Carbon, C.C., Michael, L. & Leder, H. (2008). Design evaluation by combination of repeated evaluation technique and measurement of electrodermal activity. Research in Engineering Design (19), 143–149.