Introduction

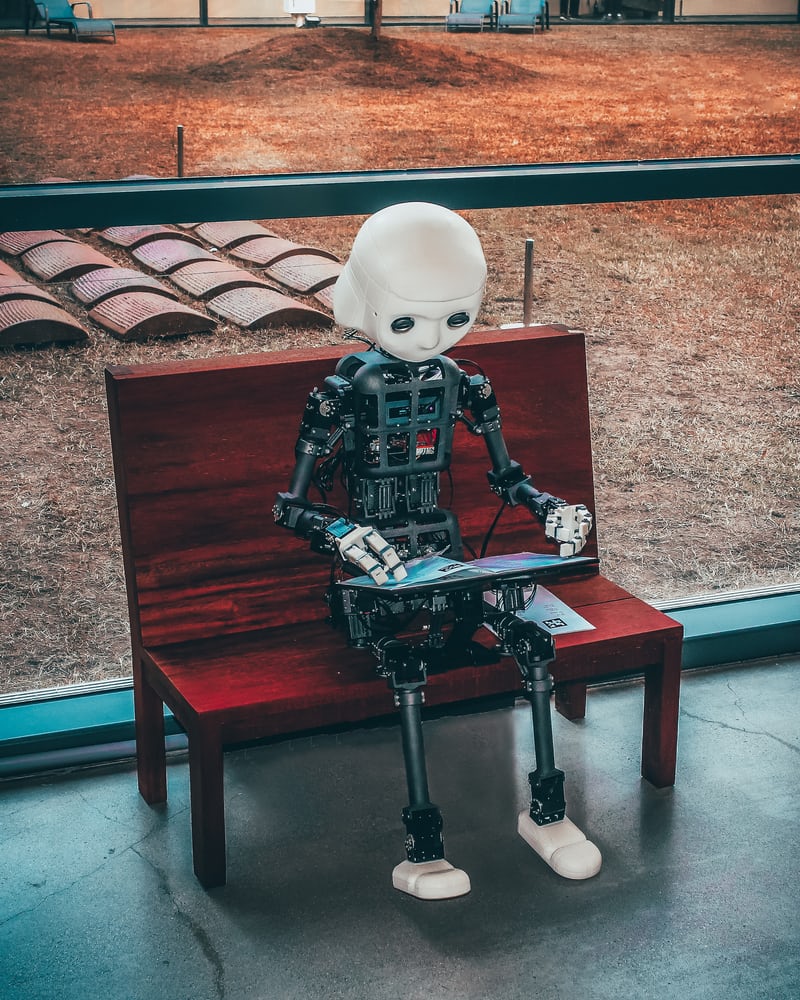

Imagine two different people making a financial decision, such as deciding where to invest in, how much to save this month or which retirement plan is the best for them. Sophia, one of our two imaginary people, is enthusiastic about technology and loves to try new gadgets. Francis, the other one, is not really into tech; he likes to think of himself as “old-school”. But both want to make the best possible decisions, obviously, and seek advice from their financial institution. The only advisor available to them is a robo-advisor; a system powered by artificial intelligence. Sophia is excited. Francis not so much. Will these different attitudes impact how much Sophia and Francis are following the AI advice when making their decisions - will Sophia’s enthusiasm help her to learn more from the advice, potentially making a better decision than Francis who dislikes the idea of getting advice from a non-human advisor?

Sophia and Francis are hypothetical examples, but research shows that some people don’t like to interact with algorithms even when it would be beneficial. This algorithm aversion can be observed not only in finance, but also in medicine, media, recruiting, to name a few. This algorithm aversion might lead people to actively avoid interacting with AI agents. But as it is the case with Sophia and Francis, many institutions do not offer an alternative option anymore for many services; AI has arrived. And Sophia and Francis could be consumers, as in our example, or they could be employees. In the latter case, a neglect of valuable advice might impact many more people, amplifying the consequences and the opportunity costs.

Given the importance of the issue, it is surprising how little we know about how people’s attitudes towards AI impact how much they take the advice into consideration. We set out to fill this knowledge gap.

In our study, 139 participants performed a series of investment choices. First, participants were given a bit of money to invest during the study. Then, they learned about different funds they could invest their money into. We used real investment funds with real financial information but changed the names of the funds. Then, they had to choose between getting advice from a financial advisor that is human or one that is an AI. The decision let us to identify if the participants was more like Sophia or Francis and had a positive or negative attitude towards AI advice.

Crucially, sometimes participants got whom they wanted (e.g., Sophia got a bot, Francis got a human), and sometimes not (e.g., Sophia had to endure human advice, Francis AI advice). This allowed us to test how what participants wanted impacted how much they used the advice. Finally, after hearing the advice, they updated their investment decisions. The better the participants' investment decisions, the more money they got as a bonus at the end of the study.

So, what did we find?

Overall, participants did not have a strong preference for either human or AI advice, some of our participants were like Sophia, preferring AI advice, others were like Francis, preferring human advice. This matches what most of us experience in real life – some hate AI, some love it, and some are indifferent. But this also allowed us to test our key question: Did participants’ attitudes impact how much they took on the advice from the human or the AI?

Surprisingly, we found that participants learned similarly from AI no matter if they preferred humans or AI. A participant like Francis that preferred human advisors, used the advice coming from an AI to the same degree as a participant like Sophia.

Our result mirrors research on so-called learning styles. People often express a strong preference when asked how they like to learn. For instance, people might claim that they are visual learners, and struggle with text. However, when tested, people who claim to be visual learners do not learn better from more visual information than people who do not claim to learn better from visual information. Similarly, claiming to not like advice from AI did not impact how much participants learned from AI.

It seems hard to believe that a lover of tech like Sophia might not have any advantage when interacting with AI advisors over old-school Francis. Was there nothing that impacted participants learning from AI? Indeed, there was.

We found that participants with higher technology acceptance, like Sophia, considered AI advice to a greater extent, compared to participants with lower technology acceptance. Participants that endorsed statements like “AI-based tools and advisors are, overall, safe and trustworthy” took in the AI advice more than the ones who did not.

This finding offers institutions and companies with a promising way to tackle AI adoption. Technology acceptance is something that can be improved. Rather than focusing on people’s attitudes—a hard exercise that is not that likely to work, companies might try to understand to what degree a person feels knowledgeable about AI technology, and provide training to improve their understanding.

Of course, this is just one study, and more needs to be learned about how people’s attitudes impact their interactions with AI, whether it is as costumers or employees. Such interactions might not only impact how people make financial decisions but might also shape underlying feelings towards the company. Francis might learn similarly from a human or an AI, but feel unhappy about the support provided to him on his financial journey, weaking his commitment to the company. And Sophia might feel the opposite.

As part of our partnership with the Dept of Psychology at City University, London, Cowry offers 2 x Research Grants to Behavioural Science Masters students.

Email : jezgroom@cowryconsulting.com for more information.

Want to learn more?

References

-

Bianchi, M., & Briere, M. (2021). Robo-Advising: Less AI and More XAI? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3825110

-

Dietvorst, B. J., Simmons, J. P., & Massey, C. (2014). Algorithm Aversion: People Erroneously Avoid Algorithms after Seeing Them Err. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2466040

-

Kahneman, D., Sibony, O., & Sunstein, C. R. (2021). Noise: a flaw in human judgment (1st ed.). Little, Brown Spark.

-

Longoni, C., & Cian, L. (2020). Artificial Intelligence in Utilitarian vs. Hedonic Contexts: The “Word-of-Machine” Effect. Journal of Marketing, November. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920957347

-

Longoni, C., Fradkin, A., Cian, L., & Pennycook, G. (2021). News from Artificial Intelligence is Believed Less. https://doi.org/10.31234/OSF.IO/WGY9E

-

Shin, D. (2021). The effects of explainability and causability on perception, trust, and acceptance: Implications for explainable AI. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 146, 102551. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJHCS.2020.102551